Schulz + Tanya Lee

We are continually inspired by Tanya's leadership in ethical and environmentally conscious manufacturing—a necessary change for this industry.

When we started designing the 1912 Pullover, I knew we needed to make something riders would be proud to wear, not just from a style standpoint, but also impact. What we wear, and the products we buy, are a reflection of our values. That's why I was thrilled to connect with Tobimax Textiles as a manufacturing partner—their uncompromising ethical and environmental standards truly raise the bar in their industry. I thoroughly enjoyed my conversation with Tanya Lee, Vice President of Tobimax Textiles, and I hope you find it just as insightful and eye-opening.

When Tanya Lee stepped up to run Tobimax Textiles, a company founded by her father over thirty years ago, she lucked out. Her father, whose business model had revolved largely around the manufacturing of polyester and other synthetic fabrics, trusted her to make systemic, unorthodox changes in the company’s model that incorporated her interests in sustainability, ethical manufacturing, and fair labor practices. Says Lee, “that’s something a lot of companies struggle with — having a new successor come in and not having the freedom to do whatever it is they want to do — and that’s really important in being able to make a change, to make an impact.”

That does not mean the transition came without challenges. At five feet tall, the daughter of the owner, and a woman, who, in her own words, “looked like a child” when she began a leadership position in the company at the age of twenty-five, Lee faced both self-doubt from within and a lack of respect from male colleagues. Remembering this time, Lee espouses an experience many women in the workplace can relate to: “nobody really took me seriously.”

Rather than cave to these pressures, Lee used this opposition to shape how she would run the company, especially in terms of labor, gender, and respect. For instance, Tobimax does not use temporary contract workers, a practice that sets them apart from standard operations in their industry. Temporary workers do not receive typical employment benefits, such as health care or pensions; they are generally hired during peak seasons, such as right before Chinese New Year and around July, in preparation for the Q4 holiday season. Tobimax, on the other hand, keeps their employees on payroll year-round, giving them a sense of financial security and personal investment in the company. Currently employees at Tobimax make around fifteen percent more than industry average, a figure Lee would like to see go up to twenty-five if she can get around resistance from people in the company “who care about numbers," she says with a smile.

About eighty percent of the company’s warehouse labor force is made up of women, which is typical in the garment industry. What is not typical, however, is that ninety-five percent of their office also consists of women, and Tobimax regularly places women in manager roles on the warehouse floor as well. Even in an industry where women make up the majority of the labor force, male employees are still often perceived as more efficient and capable when it comes to leadership positions, an idea that Lee attributes to gender stereotypes that exist everywhere but are particularly prevalent in Asia, where the bulk of Tobimax’s operations are located.

Lee became passionate about labor conditions partly because of what she was exposed to growing up the daughter of a successful business owner in the garment industry. She remembers seeing many things as a child other people simply do not see. Lee’s voice cracks as she describes one particularly harsh memory, witnessing teenagers as young as sixteen years old working in a denim factory in China, forced into employment to support their families. Lee, around thirteen or fourteen years old at the time, recalls that the constant exposure to the indigo dye used in denim production meant the teenagers hands and arms were permanently dyed a vivid shade of blue.

This trip also piqued Lee’s awareness of the sheer volume of waste produced by the industry and the need for change. She witnessed bucket after bucket of indigo-contaminated water dumped into a nearby river. She saw thousands of pounds of fabrics that didn’t pass Grade A quality standards simply thrown away. Because of these formative experiences, Lee would eventually be inspired to transition Tobimax’s production focus from polyester to recycled polyester — a subtle but monumental shift.

Lee was not always destined to be her father’s successor, however. Her position at the company came about through a series of decisions made in adulthood rather than a planned succession. After getting a Bachelor’s degree in Sociology at The University of British Columbia, Lee spent her time as many recent college graduates do: wondering what she was going to do with the rest of her life. She went back to school at Sauder School of Business where she received a Masters in Business Management and eventually moved back to Taiwan to be with her mother as she underwent treatment for cancer, a disease she fought for twenty-five years. It was during that time she started working at the family business, in the office. When she expressed dissatisfaction at various aspects of the company, her father, ever the fan and in blissful ignorance of what was coming to him, asked her what changes she would make if she were in charge.

This prompted Lee to come up with a veritable laundry list of things she would do differently, including industry attitudes that were not working and policies she believed were just flat out wrong. She jokes that she made the list with no thought to the practical realities of the changes she requested, because at the time she had nothing to lose: “I’m going to cause all this ruckus because I’m not going to be the one executing it and I’m not going to be responsible for it.” Little did she know that as she got more and more involved in the implementation of these changes, Lee slowly but surely became exactly the person executing and responsible for it, eventually taking it over.

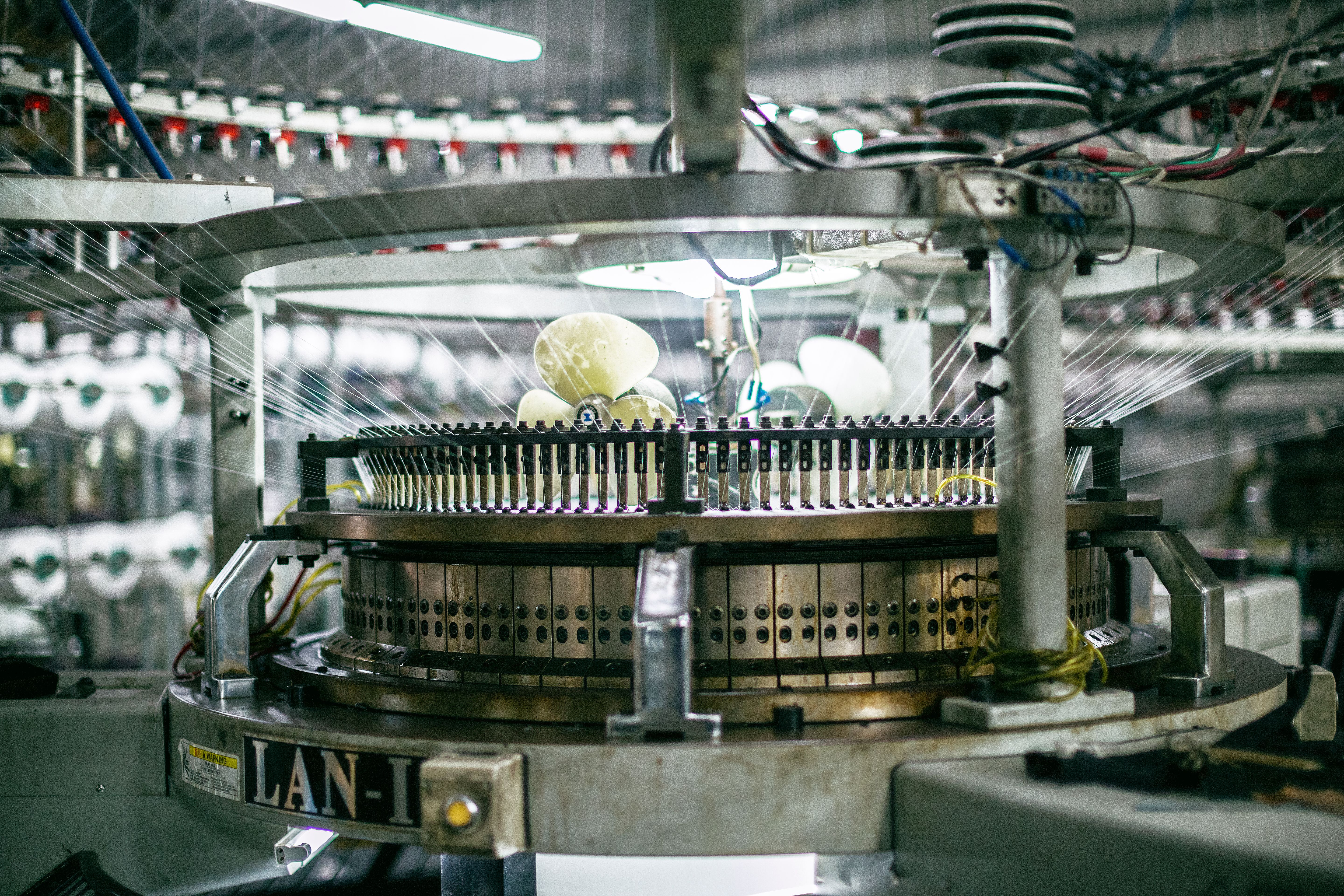

One of the many modifications she implemented was the addition of natural fabrics to their roster of inventory, including items such as organic cotton and tencel, a fabric derived from the eucalyptus tree. Buying it in small batch forms — as Tobimax did with Schulz for the 1912 Pullover — proved extra challenging, as suppliers are used to extremely large orders and tend to take a company ordering a small amount less seriously, especially when said company is spearheaded by a woman. This attitude towards cheap, bulk products is one of the foundational reasons so much waste is produced in the fashion industry’s manufacturing process. It is, in multiple senses, easier to make one hundred thousand cheaply-produced synthetic items than it is to manufacture five thousand natural and sustainably-produced items. Even if large amounts of the cheaper product remain unsold, the profit margin is still usually higher than what the small batch ones would expect.

In general, fabric manufacturers produce in bulk, which means their warehouses are also set up to do so. Because of the different techniques used in production, synthetic and natural fabrics require different warehouses for processing, which means Tobimax has to rent out facilities when they dye and treat natural fabrics, as the warehouses they own are set up for synthetic and recycled synthetic products. Again, the assumption that larger production is better production here becomes an issue, as Lee says many companies are reluctant to rent out their warehouses for smaller batches, partly because they simply do not think of it as a serious or “real” business. Here the industry’s perception of itself is key, and drastic shifts in attitude are needed internally for change to occur.

Criticism from environmentally-conscious groups can happen as well, even in the midst of industry revamping. Some controversy exists, for example, around the use of rayon, a material Tobimax uses, because, while it is a natural product, the fabric goes through a number of chemical processes in its manufacturing. Essentially, Lee explains, any time you have a hard material, such as the bamboo that is used to make rayon or the eucalyptus used to make tencel, you are going to have to process it chemically to make it go from hard (bamboo, eucalyptus) to soft (rayon, tencel). While these newer, more-sustainable processes are not perfect, they are a massive improvement on the old ones and a reflection of where we are at now, which Lee says is “a win.”

Another improvement Lee implemented has to do with their water supply. As the buckets and buckets of indigo-dyed, chemically-contaminated water Lee witnessed going into a Chinese river years ago indicates, the fashion industry has an extreme water problem. Undaunted, Lee set up facilities to harvest rainwater rather than tap into the country’s water supply. Traditionally, rainwater has been thought of as too full of minerals and sediment to be useful in the dying process because those elements make the resulting color difficult to control. Lee found that simply setting up rigorous filtration processes fixed this issue, and that with this filtration not only can rainwater be utilized, but water that has been through the dying process can be re-filtered and re-used multiple times.

Tobimax is also committed to sourcing ethically-produced yarn for their manufacturing processes. Whenever they buy from suppliers, Lee says, they ask what regions the fibers are sourced from, avoiding conflict regions such as Northern China, where the Chinese government has detained the Ulghurs, a Muslim community, for “re-education”. In these concentration camps the Ulghurs are often forced into unpaid and underpaid labor, including in the textile industry, as part of the internment process. This practice amounts to, essentially, modern-day slavery and is a part of the production of "fast fashion" — mass-manufactured fashionable clothing sold at an unrealistically low price. That low price comes at a high ethical cost.

Lee credits her experiences witnessing the indigo-stained arms and hands of teenagers at her father’s denim factory and watching her mother dying of cancer for her desire for change, citing the importance of personal experiences in changing people’s perspectives on labor and the environment. Tobimax workers benefit from this attitude, where, in addition to the above-mentioned benefits, one of the more quirky perks of employment include one-hour daily work naps. Lee sums up the philosophy behind these reforms by stating simply “the world just isn’t working the way we thought it would work, so, in order for us to survive…we need to make changes.”

Learn more about Tanya and Tobimax Textiles on their website here.