Schulz + Lauren Murphy

Schulz photography contributor Lauren Murphy on artistry in the age of social media, prioritizing connection over recognition, and loving horses after the ride.

Spend a bit of time within the world of Lauren Murphy’s Instagram account @handcraftedinvirginia. Scroll slowly, with intention, and you will notice more than meets the vertically gazing eye. You may swear you can hear the sounds of a swinging tail, or smell that oddly satisfying aromatic mixture of hay, dust, and manure. Perhaps you’ll be able to imagine so fully the velvety feel of her pitbull, Rory’s, ear, simply because the shot is so detailed, yet focused in its simplicity.

Within minutes of speaking with the artist behind the lens that is @handcraftedinvirginia, it is obvious she comes by each of her design-centric interests honestly. Her parents own a remodeling company, Murphy’s Design, and she has early memories of creatively using what she could to make her space her own. “My mom always jokes about this time at McDonald's where they had these Winnie the Pooh keychains that came with the Happy Meals,” Murphy recalls. “I made these wall hanging installations out of them. I would just hang all this stuff on the walls. Even when I was small, I was decorating.” From an early age, she could shed light and find the beauty in even the smallest, most seemingly mundane of things.

As a child, Murphy’s father, while on a job on a barn site, met someone who suggested she start riding. “I was very small,” she says, “maybe five at the time.” That barn quickly became a second home and she remained there for over a decade, amongst the same smells and smells, at which point, the land was sold for development, the first of many equine-related heartbreaks for her.

“I struggled a lot to find the perfect horse,” Murphy says.” I went through a lot of leases and lost a lot of horses. I remember every one of them, every connection, and how devastating it was to have them taken away from me, especially at that age.”

Among them: Belarus, a Chestnut Oldenburg; Gulliver, a Bay Off the Track Thoroughbred; Tuey, a Flea Bitten Anglo-Arabian; and Telsa, a Chestnut Off the Track Thoroughbred. There was also Keano, the most beautiful Chestnut Flaxen Mane who failed his vetting. Murphy recalls: “We decided to hold on to him and re-vet him in a couple of weeks, but the owner said “no” and just took him away.”

There was also Guernsey, a Liver Chestnut Oldenburg, who belonged to Murphy’s trainer and was never actually for sale, but a personal favorite. One Easter Sunday, Guernsey coliced in the middle of the night. The next day, Murphy quit riding.

I went through a lot of leases and lost a lot of horses. I remember every one of them, every connection, and how devastating it was to have them taken away from me, especially at that age.

It wasn’t until years later that she cautiously reconnected with her equestrian roots while dating a guy whose parents had horses. After their breakup, she got a job working at a barn flipping horses. “I think I started taking photos periodically throughout that time,” she remembers.

Originally, her idea was to create photography for the sake of community. After seeing website after website filled with bad photos that didn’t adequately represent the barns and horses they were advertising, Murphy decided to step in and help these struggling businesses with her art and digital savvy. “I started off by offering my services for free on Virginia Equestrian.” Murphy posted a classified ad, offering to “come out to your barn and take photos.” Without a formal portfolio to show, she sent her social media links and, soon enough, had a couple of local people reach out.

Murphy’s call-out to her community rings bold at first utterance: like a megaphone of confidence announcing her presence as an equestrian artist for hire. Instead, like many artists, the self-proclaimed introvert struggles understanding the worth of her ability and art.

“Everyone's a photographer now,” Murphy laments, referring to Instagram. “Some people have the best equipment just because they have 50,000 followers. That's hard for me because I feel like I could do so much if I just had that ‘one lens.’ But I know from experience that when I get that lens that it’s about ‘that other lens.’ It's a constant thing with equipment.”

Like many of her generation, social media -- specifically that platform of Instagram -- has proven complicated for Murphy for reasons other than just a constant feeling of keeping up with the Joneses.

“I struggle so much with social media,” she admits. “I am a human sponge and will soak in all the feelings of the whole world if I let it. I have always struggled caring what people think. For a while, I looked at ‘likes’ and how many people were following me. I assumed that my popularity on Tumblr would translate into Instagram and it didn’t. The followers didn’t come and my feelings were hurt.”

Murphy continues with an anecdote about a recent photo she posted two days prior -- a photograph of a front door that, at the time of our interview, had only received around 106 likes. “I love that photo,” she says protectively of it. “I get that it’s not a horse, but I like the color in the wood. That’s why I posted it.” As if to remind herself she says, “I know it’s a good photo. I like that photo and it shows that I am capable of photographing more than just horses.”

The above photo in discussion exemplifies just how much emotion Murphy can pack into a simple image: the juxtaposition of the brick against the blue door frame, the pop of orange seen in the shapely pumpkins, the light which is both bright and fall crisp all at once.

“I really try to work within my strengths,” she says.

Strengths like her trusted eye, which enables her to go from beautifully muted tones to saturated deep oranges...or draw attention to the details of the most minor actions of horsemanship. “I can see what I want something to turn out like in my head before I take the photo. I will look at something and know "that's a photo" and need to take it.”

Strengths like scheduling shoots according to her natural light preferences or curating her Instagram feed in advance. “The thought I put into my feed is more strategic than it needs to be,” Murphy admits, “but I just can't help myself.”

Strengths like sticking to her own personal style, which is uncluttered, punctuated by negative space, and always purposeful: “I'll find certain people’s work inspiring—like Anouk Masson Krantz’s photography in her book "Wild Horses of Cumberland Island" or the equine portraits in Koto Bolofo's ‘La Maison” Hermes Photographic Book—and I wonder if I could do something like that. But whenever I try to understand their technique, it always seems forced. I try to go into something and look at what I'm presented with and take the photo for what's in front of me. That seems to work best for me.”

Even with a laundry list of tactics, strengths, and skills, she admits to having to remind herself to let go of the stigma that “only a newb” would use tools like a tripod or autofocus. “Sometimes the stars are just not aligning, especially with a horse,” she begins. “You can't determine what horses are going to do all the time. They are moving constantly. You can't just ask them to stand still. Sometimes I just have to suck it up and let the camera do the work.”

Murphy is quick to claim photography is “75% hobby”; that she’s “not a photographer that is super technical” and “doesn’t work with fancy equipment.” But her aesthetic, passion, point of view, and heart make it clear to anyone that sees her work that she’s a true artist. “When I look at certain photos of horses, there's just something about their facial features. It comes down to the veins in their skin,” she says.

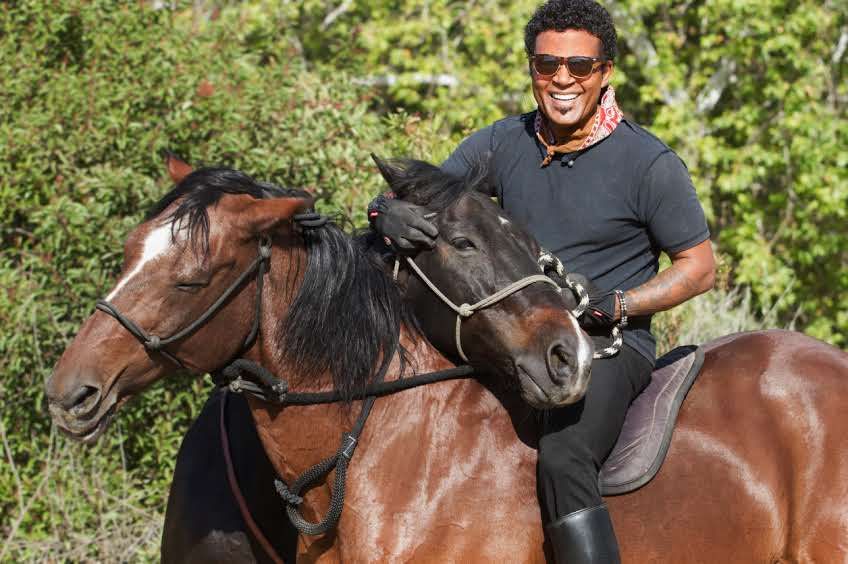

“With horses…it's a whole-body exercise where there is so much engaged at one time and simultaneously relaxed. There's just so much to photograph that doesn't revolve around a face. The most important part is the relationship,” Murphy answers when asked about how she decides what to shoot, “which is interesting since I was never really able to establish that [for myself].”

You’ll infrequently find photos of people riding on Murphy’s Instagram account—and that’s certainly intentional. Despite not being able to form her own poetic, unbreakable partnership with one horse, she spends time documenting other’s. “I want to capture the bond,” she says. “I want to see them sitting in the back next to the stall on their tack trunk hanging out. Those moments in between are when the real relationship happens between the rider and the horse and the real trust happens.”

Murphy has barely touched her camera since the beginning of COVID, after both of her parents tested positive in April. [Ed Note: Murphy’s parents are both doing well now and thankfully were asymptomatic the entire time.] “My friend has invited me out a lot to shoot, but I've been very hesitant to be around people. [My camera is] sitting here looking at me.” But she’s itching to get back behind the lens. “I want to see my people and photograph them.” A creature of habit, she can’t wait to see the horses again. “That's been difficult,” she says. The first subject on her to-shoot list: “I would love to go out and photograph my friend Jean French of The Natural Connection in Linden Virginia!”

Instead, in between keeping up with her day job as an interior designer and certified home stager, she has been focusing on looking back at past content. “It's fun to go back and look at photos! I take so many, between 1000 to 1500 photos per shoot,” she says. “I now can go back and look at photos that I've never touched before.”

Thinking on past shoots, she reminiscences: “There [are many] horses [in my photos] that you can tell have heard me and come over to see what I was doing. There's something I just love about that…just hanging out with all the animals. I could just sit down and hang out and they would move around me and come over and investigate what I was doing and then move on. I just so prefer them over people.”

Lauren’s Cause: Wild Horses

During each interview, we ask what cause or social issue he or she is paying particularly close attention to in hopes to raise awareness.

There are currently only 100 wild horses left in Currituck, North Carolina. “There's been a huge issue in the Outer Banks with people interacting too closely with the wild horses,” Murphy explains, “and a foal recently passed away because somebody fed it an apple. “Everyone wants to get that photo to share on Instagram with the wild horses, but these animals aren't used to people,” she explains. “It's important that people understand that they are wild animals.”

You can learn more about the wild horses in the Outer Banks on https://www.corollawildhorses.com/